The Nation’s History in Classroom Silence

The Nation’s History in Classroom Silence

Written by Directorate of Public Relation and Alumni Network (9/24/2025)

Contributor: Nur Hidayati - The University of Queensland

Students today are often negatively perceived as a generation that does not understand history, or as a generation without history. They are greeted by the digital world from birth. Information pours in quickly and ceaselessly through their screens, driven by algorithms that are increasingly difficult to control, pulling them ever deeper. But it’s not just social media, systems and educational curricula, particularly regarding history lessons, contribute to disconnecting this generation from knowledge of history. Ideally, history should be an essential component for every student as a citizen, not only to understand the nation’s journey but also to build self-identity, foster critical and humanistic attitudes toward the present. Yet, in practice, history teaching in schools still falls short of these ideals.

Over time, history has lost its place within the education system. The 1947 and 1952 curricula were the first post-independence curricula, imbued with nationalistic spirit, both including national history lessons from the elementary level (kurikulum.kemdikbud.go.id). The curriculum has changed nine times since then (1964, 1968, 1975, 1984, 1994, 2004, 2006, 2013, 2022), as have the structure of subjects and allocation of instructional hours. History was taught as a dedicated subject from elementary school in the 1952 and 1994 curricula, while in 1947, 1964, 1968, and 1975, it wasn’t introduced until middle school. In the 1984 curriculum and from 2004 to 2022, history was only included or integrated into Social Studies (IPS) lessons. This subject only becomes specialized at the high school level, with a condensed curriculum and limited classroom hours.

This is also the case with the current curriculum. History lessons, only present at the high school level, are allocated 84 hours in grade X, 140 hours in grade XI, then back to 84 hours in grade XII. At the elementary and middle school levels, history is not taught as a separate subject but is combined into Social Studies. Historical understanding should be instilled early and gradually developed. Without history education from elementary through middle school, young generations lose not only historical knowledge but also a sense of connection to their own nation’s history.

However, the issue is not just about quantity of time. Another fundamental problem is the mismatch between the aims of history education and its practice in the field. Take the 2013 curriculum, for example, which explicitly intends history lessons to be rich in skills and historical thinking approaches. Students should be able to link national and local historical events and be inspired by national values (sma.dikdasmen.go.id). The “Merdeka” curriculum wants students to connect past events to the present so they can project the future, train thinking skills in terms of diachrony, synchrony, causality, creativity, critical and contextual thinking, as well as being able to conduct structured historical research with both digital and non-digital outputs (Badan Standar, Kurikulum, dan Asesmen Pendidikan, 2022).

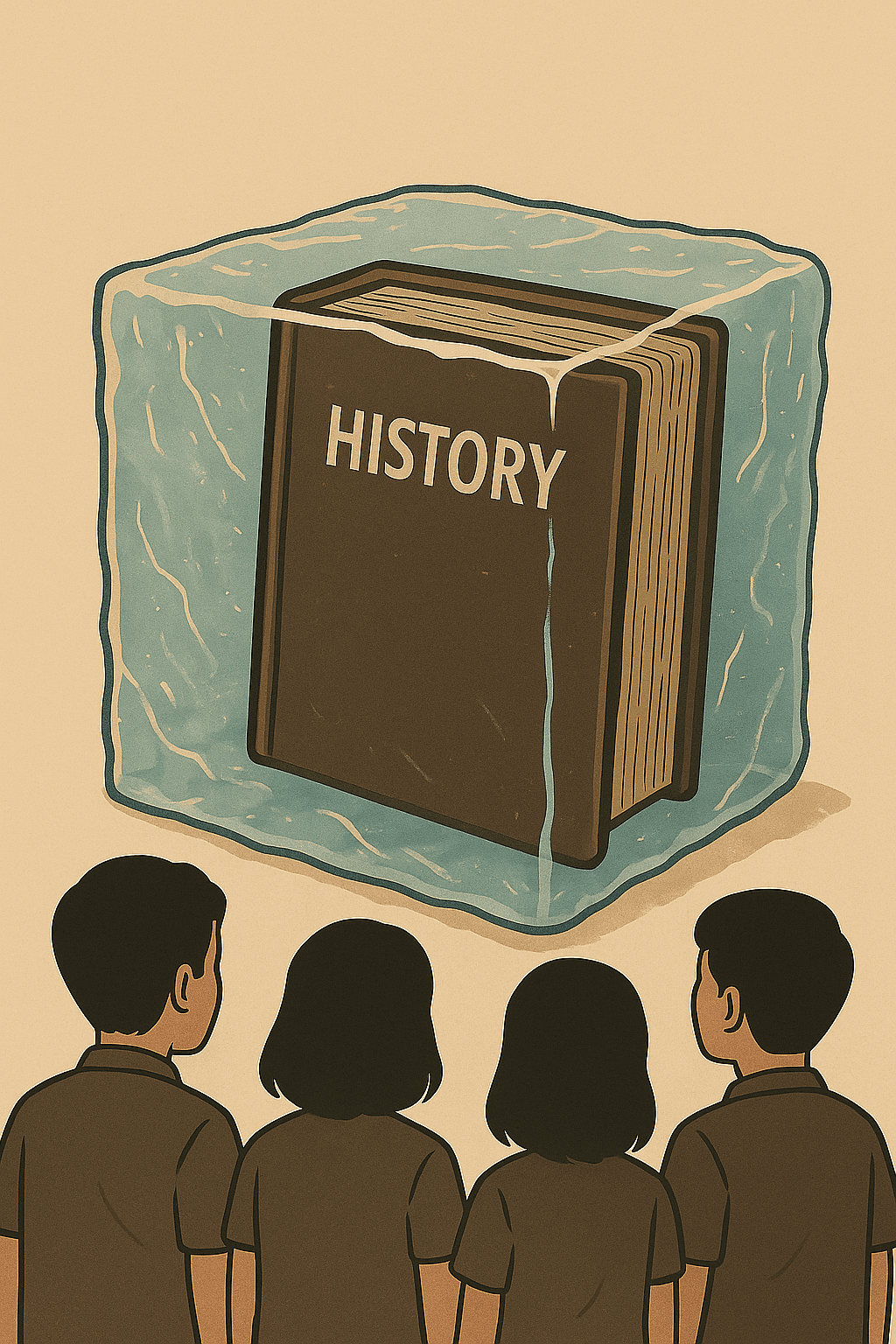

In reality, however, instead of developing reflective thinking, history class is often just rote memorization of years, figures, dates, battles, and locations, without deeper meaning. Instead of building awareness or understanding the complexity and contradictions of the past, factual knowledge required for exams is quickly forgotten once school assessments are over. This cognitive-heavy approach, neglecting contextual understanding behind every event, turns history into an abstract science, disconnected and failing to touch student consciousness. History is not presented as a dynamic dialectical process, but more like a frozen encyclopedia. Eventually, history lessons do not really foster critical power or sensitivity to ongoing injustice today. Yet history should be a space where students learn empathy, recognize injustice, and foster moral courage to confront the present.

Because history is not delivered interactively and lacks critical reasoning, historical narratives taught at school often lead to misconceptions and dehumanization of historical figures. For example, national heroes are always depicted as those who consciously “defended Indonesia,” whereas at the time, the concept of Indonesia as a nation state had not yet existed politically as it does today. The fact is, many figures introduced as heroes fought for justice, humanity, and resistance against colonial oppression, not necessarily out of a unified sense of nationalism. This kind of simplification erases the complexity and humanity of historical figures. Cut Nya’ Dien took up arms due to her anger at her husband’s murder and to resist Aceh’s colonial occupation. The Java War of 1825–1830 involved the mass mobilization of Javanese society as a form of Diponegoro’s resistance against Dutch intervention in his ancestral land.

Another serious problem in history lessons is that the material appears to stop at the New Order era. In the seven-page Indonesian History module for Grade XII (2020), the early period of reforms in 1998 is described as Suharto’s policy to strengthen state power, which triggered a multidimensional crisis (political, economic, legal, social, trust) instead of highlighting the bold actions of Reformasi 1998 that marked a major resistance by students and society against 32 years of New Order rule. This material’s portion is only one-ninth of the other core competencies in the 2013 curriculum. In the Merdeka curriculum, two out of 31 topics related to the reform era in its 84 instructional hours are only meant for students to explain the relationship between economic-political policies in early reform (1998–2000) and reform (2000–2009). Major events like the May 1998 riots, student and popular demonstrations to overthrow Soeharto, and the transition to democracy are not yet part of the school curriculum. These influential national dynamics remain absent from history books.

As the saying goes, history is written by the victors; history curricula do not just limit interpretive space but also tend to avoid discussion of severe human rights violations in Indonesia. The 1965 tragedy: mass killings, disappearances of those labeled as PKI without due process, political prison camps and their decades-long impact on victims’ families, is glossed over or omitted entirely. Tragedies like Talangsari, mysterious shootings (Petrus), state violence in East Timor, Papua, and Aceh are all nearly absent from the official historical narrative.

What’s overlooked is not just the events, but also who counts as part of history itself. The perspective of women is almost never presented in history textbooks. Women are usually mentioned only as wives of important figures or occasionally as participants in struggle, even then depicted mostly in passive and domestic roles. In fact, women were often direct victims in many historical events. For example, in the 1965 tragedy, thousands of women were arrested, tortured, and sexually assaulted for allegedly being involved with Gerwani, yet they were never given space to speak publicly. Their stories are almost never found in history books, especially in classrooms.

The same applies to certain racial and ethnic groups. The May 1998 tragedy left deep scars on Indonesia’s Chinese community, from looting, arson, rape, to systemic violence. Yet their experiences are almost never recorded in school history books. In the grand narrative of rewritten history, they continue to be positioned as “the other,” not as Indonesians who suffered and deserve recognition.

Ironically, much of the research on history education focuses on cognitive issues such as learning outcomes, low test scores, or poor material absorption, rather than critically examining the philosophy of history education itself: Does this lesson cultivate humanity? Do students become more empathetic toward victims of human rights violations? Can they distinguish propaganda from historical fact?

In the absence of critical history teaching at school, new spaces of historical discussion are increasingly occupied by non-historians. Content creators, influencers, even politicians deliver their own versions of historical narrative. Popular history books or historical fiction are sometimes chosen by those seeking a more digestible version of historical truth. Unfortunately, not all authors on history understand and adhere to historical writing methodology. Although this phenomenon is not wholly negative, there are considerable risks if the historical narrative is shaped by those who do not use scientific and critical approaches. Historical works, even in fiction, must still apply the stages of historical writing, including gathering sources from the closest and most relevant era and verifying source authenticity and accuracy before interpretation and presentation.

All those concerns aside, we now face another challenge: rewriting of the national history. The question is, does this effort aim to enrich perspective or to simplify the narrative for certain interests? If the agenda for rewriting history does not reflect the diversity of voices and merely serves to filter reality, then history books will truly lose their soul. They will cease to be a tool to understand the past comprehensively, becoming instead a mechanism for mass forgetting. We will be taught to remember only victories, heroes, and achievements—not wounds, failures, and betrayals.

What we need today is not just more hours of history lessons, but a history that truly sides with truth. History that gives voice to those who have long been silenced, victims of violence, forgotten women, marginalized ethnicities, and communities deemed unimportant in the grand narrative of nationalism. The issue is no longer just about questioning history lessons and refining curriculum content, but about how history can be written inclusively by all elements of society, serving as a space for reflection for every citizen, and delivered openly especially to students as the next generation, as lessons from the past to anticipate future mistakes and shape national aspirations.

References:

Adam, A.W. (2006). Pelurusan sejarah Indonesia. Ombak.

Farid, H. (2005). Indonesia's original sin: Mass killings and capitalist transition, 1965–66. Inter-Asia Cultural Studies, 6(1), 3–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/1464937042000301123

Kemendikbudristek. (2022). Capaian pembelajaran SMA/MA Kurikulum Merdeka. Ministry of Education, Culture, Research, and Technology.

Lim, M. (2017). Freedom to hate: Social media, algorithmic enclaves, and the rise of tribal nationalism in Indonesia. Critical Asian Studies, 49(3), 411–427. https://doi.org/10.1080/14672715.2017.1341188

McGregor, K. (2007). History in uniform: Military ideology and the construction of Indonesia's past. NUS Press.

Noor, F.A. (2021). Rethinking the nation: Historical writing in contemporary Indonesia. ISEAS Publishing.

Purdey, J. (2006). Anti-Chinese violence in Indonesia, 1996–1999. University of Hawaii Press.

Ricoeur, P. (2004). Memory, history, forgetting (K. Blamey & D. Pellauer, Trans.). University of Chicago Press.